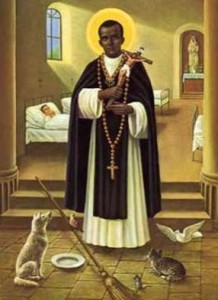

During the sixteenth century Africans and their descendants outnumbered Europeans and their descendants in Lima, Mexico City, and Salvador da Bahia–the three principal cities of colonial Latin America. Over the next three centuries millions of Central Africans and West Africans were forcibly migrated to work the plantations, mines, and in the cities of Spanish and Portuguese settlers. While resistance to slavery took place at first point of contact in Africa, continuing throughout the Middle Passages and in the Iberian colonies themselves (in the form of armed rebellions and maroon settlements, among other strategies), many enslaved Africans and their descendants assimilated into the existing colonial systems and Native American communities. Benkos Biohó of Colombia (New Grenada) and San Martin de Porres of Peru are two figures that give expression to the African Diaspora in Latin America during the seventeenth century. The former became the best-known maroon leader of Palenque de San Basilio (the oldest and longest lasting maroon settlement in South America) and the latter becomes glorified by the colonizers themselves as an exemplar of the Catholic Church (becoming the first person of African descent in Latin America to be made a saint). See the Afro-Latin American/Latinx Studies Project at UNC Greensboro.

Articles, Chapters, and Reviews:

(Photo: Richard Price, Omar Ali, and Sylviane Diouf, New York Public Library, June 11, 2015) Presentation by Omar H. Ali, “Benkos Bioho: African Maroon Leadership in New Grenada,” as part of Maroons Revisited: History and Stories, presented by the Lapidus Center for the Historical Analysis of Transatlantic Slavery, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

(Images: at top, 19th century Afro-Peruivan painter Pancho Fierro, four daily scenes; bottom left, map of palenques in Colombia; center, book cover Atlantic Lives; and, right, San Martin de Porres, 17th century Afro-Peruvian Catholic saint)

“Benkos Biohó: African Maroon Leadership in New Grenada” in Atlantic Lives (Brill, 2014)

by Omar H. Ali

The history and legend of the seventeenth-century African maroon leader Benkos Biohó is among the most dramatic of the Atlantic world. Captured and enslaved along the shores of Guinea-Bissau, West Africa, Biohó was shackled and shipped to New Grenada (in present-day Colombia) in 1596. Within three years of his arrival to the port of Cartagena de Indias—the principal point of entry for Africans into colonial Spanish South America—Biohó organized a slave rebellion, leading thirty men and women into the forest south of the city where he formed one of the earliest maroon communities in the Americas. From his maroon settlement (palenque)at the base of the Montes de María, Biohó launched multiple attacks on Spanish authorities. The attacks went on for fourteen years, until 1613, when the colonists negotiated a peace settlement with Biohó, who had become known as ‘el rey del arcabuco’ (the king of the swamps). Six years later, however, the treaty was betrayed by the Spanish and the African leader was executed. Although Biohó was dead his palenque and spirit of rebellion lived on, haunting colonial authorities for generations to come. The image of Biohó, protected by treaty, walking freely into Cartagena ‘con tanta arrogancia’ [with such arrogance], dressed in Spanish gentleman‘s attire, with sword and golden dagger at his side, seared into the minds of the Iberians.Such audacity by an African in a Spanish stronghold could only be tolerated for so long; such audacity would also inspire ongoing rebellion among captives who followed in Biohó‘s footsteps into the forests. Over the next two centuries, successive maroon leaders in New Grenada bore Biohó‘s name, or variations thereof, as a tribute to their predecessor. Biohó, the person and the name (if not title), had effectively become synonymous with African resistance to slavery in New Grenada.6 Soon his story would form part of the growing body of folklore in the Atlantic world—of heroes, villains, and rebels, including those of other notable African maroon leaders: Nyanga of Veracruz (Mexico); Miguel of Barquisimeto (Venezuela); and Ganga Zuma of Palmares (Brazil) …