Building Bridges through ‘Yes, and’:

A Methodology of Empowerment, Creativity, and Joy

Omar H. Ali, UNC Greensboro

Executive Summary for The Oliver Max Gardner Award Nomination, UNCG 2021

My philosophy is simple. It is practical and engages racism, and other forms of discrimination, as well as the deep divisions within our nation and world by providing a developmental and creative way forward. What is it? (1) We are all connected, (2) we can help each other grow, and (3) we can do so by consistently relating to each other as capable of doing things before we know how to do those things. How do we do this? By paying attention to each other, affirming our shared humanity, and creatively building on what others say or do. ‘Yes, and’ is a way of describing the spirit of this simple yet powerful approach. Although the term comes from the theatre world, the ways in which I practice and help others practice this approach is inspired by the work of teachers, artists, musicians, scientists, healthcare workers, community organizers, parents, and caregivers. In a word, people—all of us—who, in our most generous and attentive moments, relate to others as growing and capable of all kinds of things. Among those whose specific insights I draw upon are Lev Vygotsky, with his understanding of development being something humans create socially; Lois Holzman, who speaks about the creative power of play and practical philosophizing; and Carol Dweck, known for her ‘growth mindset.’

The activity of relating to others as developing—which might be understood as the increased capacity to recognize opportunities and acting on them positively—is what allows us to learn and grow. And if we begin with the premise that we are all connected (being that we are made of the same elements born of the supernovae that produced the chemistry that produced the biology that produced the societies we create) everything that follows is easier. That is, all flows more easily when we see each other as part of each other, as opposed to seeing each other as separate and in opposition to each other, which we do when we pit ourselves against each other using rigid categories and labels. Are there differences among us? Yes. These largely cultural differences have their own histories based on power, migration, and geography. However, in my experience, having a non-defensive, open posture, and ‘yes, anding’ each other (which does not require agreeing with others, but creating and building with others), and doing so rigorously, leads to collective growth, creativity, and even joy.

For the past twenty years I have been practicing this approach through my teaching, public lectures, media appearances, publications, workshops, public conversations, and through the relations I build. The Quakers might describe this approach as looking for the light in others. This resonates with me. The task is to amplify this light amidst much darkness in the world. Let us tap our collective imagination, knowledge, and creativity. We have a better chance of helping the world if we take this attitude of gratitude and shared growth. Or, put another way, we are only as good as we make each other. This practice of method—affirming of our inseparability and doing so consistently with all people (especially those with whom we disagree) takes as much faith as it does rigor, discipline, and joy. It is an antidote to the deeply troubling times we are living in and helps us build the bridges we so desperately need.

Summary of Recent Accomplishments

Given the extraordinary divisions in the world along racial, ethnic, class, and ideological lines, what is missing from conversations about ‘building bridges’—a critically important thing to be doing to find meaningful solutions to poverty, polarization, racism, and other forms of discrimination that create pain and suffering in the world—is a methodology. In other words, how do we build bridges and work together? My practical response is seemingly simple, yet powerful in its impact. It is to practice a method which might be described as ‘Yes, and.’ Derived from improvisational theatre, when trying to create a scene on stage, performers build on what each other does or says, avoiding to negate each other, by working with some aspect of what another performer gives them and creating off of this. Good conversationalists do this, effective teachers and mentors do this, and we can all do this with and for each other.

I have been practicing this approach in intentional, deliberate, and systematic ways for nearly two decades. I do this through my teaching, public lectures, media appearances, through my publications, workshops, public conversations, and in the relationships I build with an array of people and the connections I help make between people. Doing this, day in and day out over the course of many years, has yielded meaningful results, contributing to the empowerment, creativity, and joy of others. How many? I don’t know, but perhaps in the thousands directly, maybe tens of thousands indirectly when we begin to count the ways others have adopted this posture of openness and practice of method.

Grounded in the work of the early twentieth century Russian educator Lev Vygotsky, I have come to understand the importance of creating environments (conditions, contexts) for people to choose to grow—a moment-by-moment activity. In other words, things don’t just happen; people make things happen, including their own development, which is empowering. From the American psychologist Lois Holzman, I have come to appreciate the ways in which being playful, curious, and philosophical (trying things out and asking questions) can be so effective in building with others and organizing developmental conditions. And, from Carol Dweck, the issue of posture, or the ‘growth mindset,’ which sees people as emerging, resonates with the historical ways in which I see the world—as an ongoing process of becoming.

There is much more to say about the intellectual influences on my practiced approach based on the work of others (after all, we’re always borrowing and creating with what there is in the world, including ideas), but let’s get to some examples, or ‘accomplishments’ that are as much mine as they are of the many people with whom I’ve had the honor and pleasure of working over the years. These include examples in my teaching and mentoring, lectures and workshops, media and documentaries, publications, public conversations, as well as the organizations, research networks, associations, and other groups I’ve helped to create and develop alongside others. These recent accomplishments are examples that speak to contributions to the welfare of the human race and, in particular, the welfare of UNC Greensboro, where we work to create a culture of care.

Teaching and Mentoring

I continue to teach several classes a year despite being relieved of all teaching responsibilities since my appointment as Dean of Lloyd International Honors College. I have chosen to continue teaching on a volunteer basis because it allows me to grow and be close to the students who make our campus shine so brightly. Additionally, I work with students on independent study projects, oversee Honors theses, as well as serve on both M.A. thesis and Ph.D. dissertation committees in several programs and departments. At any one time I have up to half a dozen students who work with me outside of teaching my courses.

Most recently I taught “Philosophy, Science, and Race in World History,” as a way for students to engage the historical, political, and philosophical foundations of ‘race’ and the development of institutional forms of racism in the world. I also regularly co-teach an Honors and McNair Scholars seminar entitled “How do we know what we know?: Power, Epistemology, and Methodology” with Nadja Cech (the distinguished professor of chemistry). We explore different disciplinary approaches in the natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities. And I also recently taught a course entitled “Africans in the Greco-Roman World” with Rebecca Muich (a classical philologist), in which we challenge the ways we have come to understand the ancient world through our modern lenses. In this course, as with all my courses I teach or co-teach, I try to help students examine the subjectivity of interpretations of texts or other primary sources and data. We cultivate a philosophical culture in our classrooms, where I explicitly talk about how to question and build on what we are exploring together. We do so in performative ways, which, for some, become new ‘habits of mind’ and action.

My approach to teaching is similar to how I work with students individually on projects, theses, or dissertations. I take them seriously and relate to them in affirming and encouraging ways, always looking to build on what they say or do. (I think here about my former student Destiny Brooks, a white working-class young woman who wants to be a librarian; she became the editor of an interdisciplinary undergraduate journal I helped to launch with her). By doing so, over time students gain confidence and grow—sometimes in extraordinary, even breathtaking ways (as with another former student, Aliyah Ruffin, now a mother and public school teacher from a black working-class community, who took it upon herself to travel all the way to China, having only once travelled outside of the state before this). The nurturing approach I try to cultivate is especially important for first-generation college students and students of color, who sometimes need that person in their lives who simply, unequivocally, and consistently believes in them, as others believed in me.

Public Lectures and Workshops

I regularly lecture across the state, country, and world. Among the places I have spoken are at United Nations headquarters in New York, as part of events regarding the “International Decade for People of African Descent.” The panel of which I was part included the Ambassador of Brazil among others working in the fields of law, film-making, and non-profit management. I was brought in as a historian of the Global African Diaspora, and spoke about the connections of African-descended people from Latin America to South Asia. Here, as elsewhere, I try to show the interconnections between people across the globe—in this case, among African-descended people in the Atlantic and Indian Ocean worlds. As part of my public outreach, I served for eight wonderful years as a Road Scholar for the North Carolina Humanities Council, where I spoke about “Black History as American History” and “The Many Faces of Islam” at local libraries, community colleges, and museums. Many of my trips took me to rural areas where I enjoyed creating conversations with fellow North Carolinians from a wide range of backgrounds.

With the pandemic, I have also been part of numerous virtual roundtable discussions. Recently, for instance, I was on a panel organized by colleagues at the University of Chicago’s Center for the Study of Race, Politics, and Culture which examined “Youth, Race, and Populism.” I also did a similar panel on “Populism and Race” as part of the John F. Kennedy Institute for North American Studies at Freie Universität, Berlin. What I find most interesting in such panels, roundtables, or with keynote addresses is the question and answering at the end of the presentation. It’s in the Q&A that I feel that I am most able to deepen and show connections and the ways things might overlap. It is the reason why I always prefer going last on panels, if given the opportunity, so that I can try to synthesize what others have said and help create new ways of looking at a topic (effectively ‘Yes, anding’ colleagues).

Being a moderator or facilitator of conversations is perhaps one of my favorite activities. I am regularly called on to speak about or serve as a moderator. I was honored to facilitate a conversation on issues of diversity for the U.S. District Court in Greensboro by Chief U.S. District Justice William Osteen, after which he sent me a letter noting: “I was highly impressed by your abilities as a moderator. That’s not an easy task to listen, consider, and thoughtfully provoke further discussion.” This was ‘Yes, and’ in action. In addition to discussion about charged issues, I also get called on to do workshops on pedagogy, such as one I gave in Paris just before the pandemic as part of my work with the French Ministry of Education. This gathering was for a group of teachers from around the world teaching the French baccalaureate curriculum.

The key to facilitating or moderating discussions or leading workshops—whether for teachers or, as in the case on my campus, facilities workers, nurses, or other colleagues—is to listen carefully and look for connections between participants, and bring those out, along the lines of what Judge Osteen noted.

Media and Documentaries

I was recently featured on the PBS documentary “Reconstruction: America After the Civil War,” which received The Alfred I. DuPont-Columbia award. As one of several historians, I was asked in particular to speak about the Populists of the late 19th century. I offered my scholarship on the ways in which African Americans and white Southerners were able to briefly work together, despite their differences and the rising tide of attacks by the southern elites to pit them against each other. The documentary has been broadcast several times nationally and seen by millions of people across the country.

Over the summer, in the midst of the Black Lives Matter protests, I appeared on French-language Canadian Broadcasting Corporation television to discuss the movement underway in the United States. Using my ability to speak other languages, I try to accept media requests that can shed light in other countries and with a range of audiences to provide a nuanced understanding of American life. In this vein, I also did a TEDx talk to demonstrate the ways in which identities can be used and abused. That talk, “What’s in a Name?” has been viewed nearly 70,000 times. I was recently told by a former student, Stephanie Orosco, now teaching AP U.S. History in Goldsboro, N.C., that she uses it to teach about the multi-dimensionality of American society in her history classes.

Finally, I am regularly called upon (this has been sharply accelerated by the pandemic) to speak on podcasts and YouTube channels (prior to the pandemic I also did local NPR radio, among other broadcasting, including multiple appearances on CNN). Most recently, I spoke on a podcast that was in Bangalore, India, on the life of Malik Ambar, a 17th century African who rose to power from slavery to become the de facto ruler of a Sultanate in western India. Here I challenged the audience to think about the ways in which Africans have played a leadership role in world history, including across the Indian Ocean. Through media appearances, including being interviewed for documentaries, podcasts, and the like, I try to offer new ways of understanding movements and people that show their complexities and struggles—or, put another way, their humanity.

Publications

Having single-authored a number of books—that is, beyond the many chapters and articles I have published—I am increasingly working on co-edited projects with junior scholars, and sometimes graduate students, such as my former graduate student Purvi Sanghvi. We developed her master’s thesis into an article this Fall that has now been widely viewed through Live History India. I have been doing more of this co-authoring and co-editing the past few years in part because of the limitations on my time to do monographs but also because I am able to give my authority and experience (and connections to publishers) to help junior colleagues grow and succeed. Most recently, I completed co-editing Afro-South Asia in the Global African Diaspora, a three volume project with 34 contributors from around the world. I worked with three other editors, and served as the lead editor on the project because of my reputation as a scholar in the field but also my ability to organize authors and help move publications along. ‘Yes, and’ was vital in bringing this to completion.

Even as I work on new book projects with others, including two documentary source books (one with Hackett Publishing and the other with Oxford University Press), my older books seem to have had lasting relevance, prompting a second edition, for instance, of one of my first books. In the run-up to the 2020 election, I was asked by Ohio University Press to write an updated introduction to a book I published in 2008. That book, In the Balance of Power, also has a forward by the Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Eric Foner and an afterword by Jacqueline Salit, with whom I am currently working on another book called Independent Century, in which we explore the rise of independent voters in the U.S.

The work I do on the African Diaspora and the political history I write about both share one thing in common: their subjects are considered outsiders. In my writing and research I try, as best as I can, to give voice to the voiceless, with all the integrity and attention such historical players deserve. It is perhaps for this reason that I am asked to write on a range of topics that are lesser-known but have drawn greater attention lately because of the state of our world, which is in flux and struggling with whose stories we tell, and why.

Public conversations

Another way I try to reach new audiences with my approach is through public conversations. Over the years I have held such conversations with an array of fascinating people. Among those with whom I’ve done public conversations are Rhiannon Giddens, the Grammy award-winning musician, Alan Alda, the actor and director, and Lenora Fulani, the first woman and the first African American to get on the ballot in all fifty states running for U.S. President. Now that we are not doing as much in person, I co-launched a podcast called the “Yes, and Café” which serves as a way to have such ‘public conversations,’ including with the noted developmental psychologist Lois Holzman. It is also important for me to bring out the voices of the lesser-known—i.e. ordinary citizens. Local musicians, cooks, students, and teachers, have also joined us as guests on the podcast.

In addition to these containable areas—teaching and mentoring, lectures and workshops, media and documentaries, publications, and public conversations—there are a number of other ways in which I infuse the spaces I am fortunate to be in with a ‘Yes, and’ approach. Such accomplishments include producing a TEDxUNC Greensboro (having been a speaker a couple of years prior) in which I carefully curated a broad range of voices around the theme “Empowerment”; I also led the “Race and Racism in American History” forum series in the summer and into the fall of this year; I helped to create the “Underground Railroad Tree” experiential learning exhibit—a project co-created with students, faculty, and artists in the community. We looked at the Underground Railroad through a multidisciplinary perspective showing the overlap between the historical human networks of anti-slavery Quakers and African Americans and making ties to the interconnections in the natural environment, from the mycelial (fungal) networks under the trees to the wider ecological system of the forest. By making these connections, we hoped to draw out not only the ways in which people supported each other in the Underground Railroad system but the symbiotic and nurturing relationships we find in the broader ecology.

Always willing to push the boundaries, my inclination is to either get rid of boundaries or create new kinds of configurations that blur or cross boundaries—in academic terms, that are trans-disciplinary. I have done this by bringing faculty together across different disciplines, as with the Islamic Studies Research Network, the Ethiopian and East African Studies Project, and the Afro-Latin American/Latinx Studies Project. These are all projects I helped to co-found with junior faculty members, positioning them to assume greater leadership, learn, and grow—and always (always) supporting them in their creative empowerment and development.

The methodology I practice and the people with whom I have the honor to work with make this possible. At the end of the day, there are many possible ways to help each other. We can help others through charitable acts, by developing life-saving medicines, creating beautiful works of art or performances, inventing new technologies, raising funds for a cause, or lending a hand or smile. All of these are important and should be applauded and celebrated. What I propose here, and have tried to live and practice, is doing any and all things with a little more ‘Yes, and’ and a little less ‘No, because’ (all the reasons we tell ourselves and others why things are not possible). I say, let’s not only do the impossible, let’s do the unimaginable—something created before we know.

***

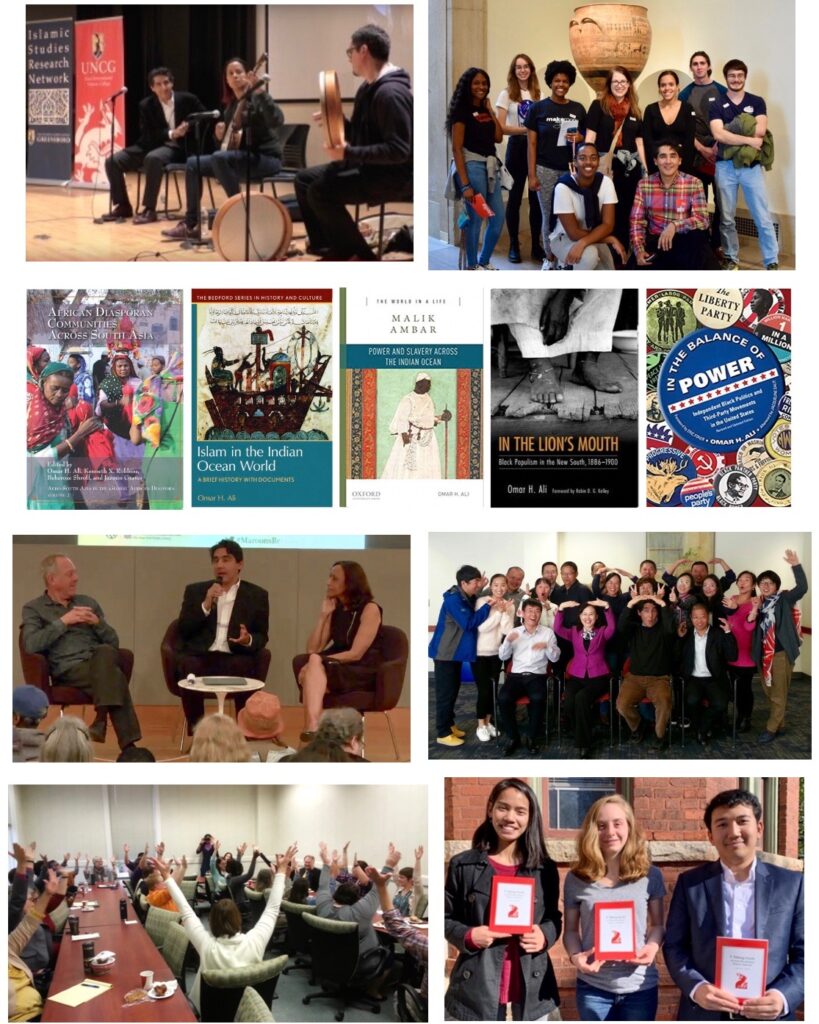

What follows are images that visually capture a range of activities that I have alluded to or activities and projects mentioned by my wonderful and generous letter writers. If you would, please take one minute to look at them and see the power, creativity, and joy in these images.

We see what we look for. And in this way I encourage us to look for the power, creativity, and joy in each other—the light in each other—as so many have done for me. We can do so intentionally, deliberately, and generously.

Join me.